Tucked away in a refurbished industrial yard in East London lies a leafy corridor surrounded by the workspace for a larger artist ecosystem. The pathway’s bright green ferns and small, bushy trees contrast starkly with the grey concrete of the building on both sides- the office and studio space, and the gallery overlooking this from the top of the stairs. This is Cell Project Space, and their flexible, reactive location is the groundwork for a space for creatives to work on projects while still allowing a huge array of flexibility. This fluidity allows artist growth and sparks community conversation.

Their current show, Daydreamers, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, is a culmination of works from Majd Abdel Hamid throughout the process of over a decade, initiating what the artist describes as ‘textures of memory’.

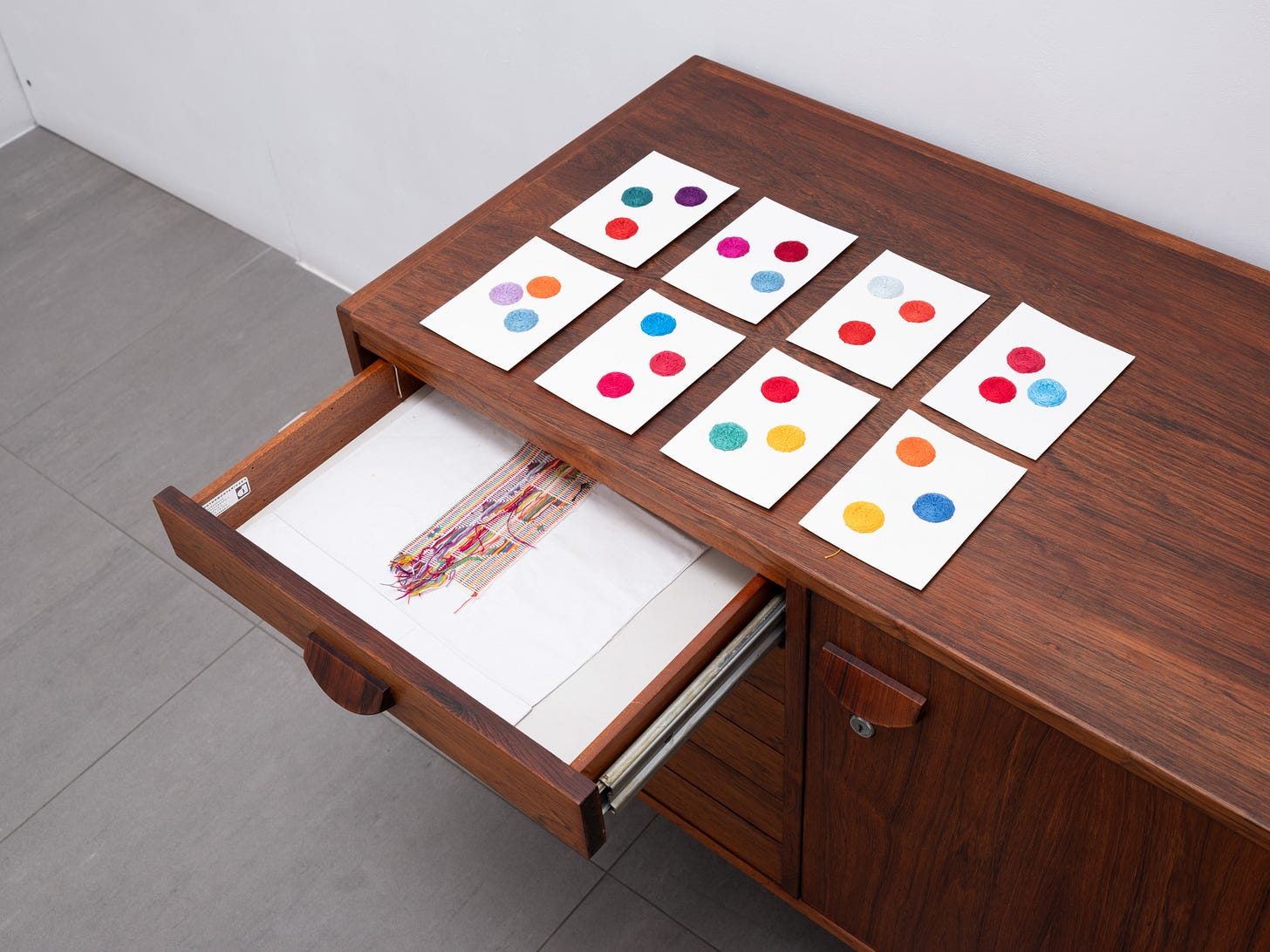

Downstairs I feel entranced in a tradition I have fallen in and out of all through my life. Sitting down, losing track of myself, between the plans and the mundane chores that had filled that day, I started passively trawling through old compartments. Is it boredom or escapism that pushes this elbow jerk reaction and pulls out drawers with it? Surely every person has cleaned their room and spent hours going through old photo albums, not just to procrastinate, but to unfold the past. The exhibition is divided into upstairs and downstairs, and benefits from a more clean approach in the upper gallery, while below, a chest of drawers and a few smaller pieces remain the main attraction. This space remains more intimate, closer to a room from a house than a dalliance through the white cube.

There is a special variable in this piece. A pair of silken gloves rest on the drawer top, inviting the viewer to handle with care. As I open and close the separate sections of the chest, I watch fragments of the work appear and reappear, arranging next to one another if I layer them accordingly, like a heightened format of picture collage. The drawers emerge like polar points, layered and working in tandem, but never merging or crossing borders.

Majd Abdel Hamid (2012–2023) 12 to 23 (End of Chapter). Cell Project Space. Image: Varvara Uhlik.

Within each compartment, I discover different choices of material, such as postcards, tissue paper, and textiles. A common thread runs among these pieces, as they all employ Hamid’s skillful use of embroidery, and expands it to a collective group. In 12-23 (End of Chapter) (2012-23), the artist found a collective of eight women across different villages, who embroidered eight portraits of Mohamed Bouzazi, a Tunisian fruit vendor who’s self immolation on the 17 December in 2010 sparked the Arab Spring. The nine pieces were brought together and left to erode for a decade, leaving behind the original threads that were reused to sew Bouzazi’s name onto the piece, acknowledging the ebbing and fading through ten years of geo-political displacement.

Hamid’s usage of embroidery is influenced by his Palestinian heritage, and a daily meditative practice. Based between Beirut and Ramallah, Hamid employs embroidery as a method to honour and contrast time-intensive processes, playing out thoughts through experimental patterns. The preservation of heritage and identity using embroidery is integral to Palestinian culture and lineage, and traces the diversity between different villages through tatreez patterns and thobes. More and more, with the scale of the ongoing genocide and erasure happening through the war on Gaza, Palestinian embroidery patterns preserve a culture that is rooted not only in its rich diversity, but the collective identity it has embraced under one flag. Such thobes, threaded with red, white, green, and black, began to appear during the first Intifada protests (1987-93) where nationalistic motifs and freedoms were severely curtailed.

Hamid contrasts warm organic household materials with colder substances like metal that often appear to be aged or worn. On a wall facing the drawers is Daydreamers (Mesh) (2025), where a smattering of soft white stitches overlaps over the mesh of a rusty radio speaker. This technique is akin to the mediums I often see used by artists such as Mona Hatoum, and deliberately forces together comfort and what lies between it.

Majd Abdel Hamid, Exhibition view (2025) Daydreamers. Cell Project Space.

The airy upstairs gallery at Cell Projects is inhabited partly by a continuation of Hamid’s series Son This Is A Waste of Time (2015- ongoing), which began when he first tried to commission a woman to embroider a piece of paper. She responded saying: “Son, this is a waste of time.” So Hamid has instead taken on the arduous process himself, imbuing each piece with the personal labor and hours spent in practice. Something inherently inverse is wrapped up in the choice of threading paper, and I am caught in the fractured momentum of it, feeling as though the page is too delicate to carry its companion thread. These pieces spoke to me as a choice to capture fleeting time or space, and they resound softly with a viewer who consistently travels between countries and homes.

Majd Abdel Hamid (2015- ongoing) Son This is a Waste of Time, Cell Project Space.

A similar theme seems to play out in Daydreamers (Fortune Tellers) (2025), Hamid’s newer series of upcycled fortune tellers comprised of scrap fabrics. Unlike the traditional Japanese children’s game, these fortune tellers hold no writings on their sides to determine one’s luck. While there is an open-ended message here, it rings neither positive nor negative, possibly negating chances in its vast ambiguity. On until the 25th of May, the artist offers each careful craft as a free gift in the last two weeks of the show. I went early on, and found a cleanly laid out rectangle of origami sculptures on the floor. I wonder if, as the final weeks pass, the shape will dissipate, and lose clarity, much like the individual fortunes.

Majd Abdel Hamid (2025) Daydreamers (Fortune Tellers) Cell Project Space.

The instinctive drive that Hamid takes to his embroidery exists somewhere in the transition between one thing to the next, and often left me in the fray with his pieces of straying threads. There is a gentle unease to this, but only in accompaniment to the acknowledgment of shifting formats and displacement: an acceptance of liminal existence without an expectation of an anchored location. The viewer is invited into an exhibition that provides an in flux analysis of geographies and the people who inhabit them. Most of all, I am carried by the care and focus that angles the pieces towards a positive approach, even in response to grief, loss, or suffering.

*Images courtesy of Cell Projects.

So interesting - Daydreamers (Mesh) 2025. I think I see a figure, maybe a lamb (wearing a stocking hat?) looking up at a night sky with moon and constellations on display. I also wonder why Hamid tried to commission someone to stitch paper. Did he want to see how they might approach the work? Why was it so arduous? Thank you for sharing this!