Ab-Anbar is one of my favorite galleries in central London. There is something poetic in its careful conceptualisation, all the way down to its name, meaning ‘water reservoir’ in Farsi. Originating from Iran, the gallery converges on meaningful diasporic connections, fluidly cultivating art and culture through varied programming.

I visited recently to catch Earendel by Hessam Samavatiam, a truly dynamic exhibition that stretched one medium in more ways than I previously conceived. I’m not always naturally drawn to photography, but the artworks by Samavatiam push film to its limits, allowing it to cradle more sculptural forms. Exposures and emulsion can be found on paper as well as ceramic or aluminium, leaving behind traces, shadows, and rising and falling horizons. At first glance, seeing the ceramic series Untitled, 2023, I am reminded of ashy craters on a distant planet. I must be partly influenced by the name of the exhibition, that refers to a star billions of light years away. The artist is interested not only in Earendel, but in the journey between it and an astronomer’s telescope, a view that is tied inherently to light and the distance it travels. This relationship to the past, memory through camera lens, and unclear meanings sets forth a precedent for the works to come. Each piece is a footprint left with no clear path forward, tied to a larger displaced constellation.

Hessam Samavatiam (2023) Untitled. High-fired ceramic, photosensitive emulsion, analog photographic process.

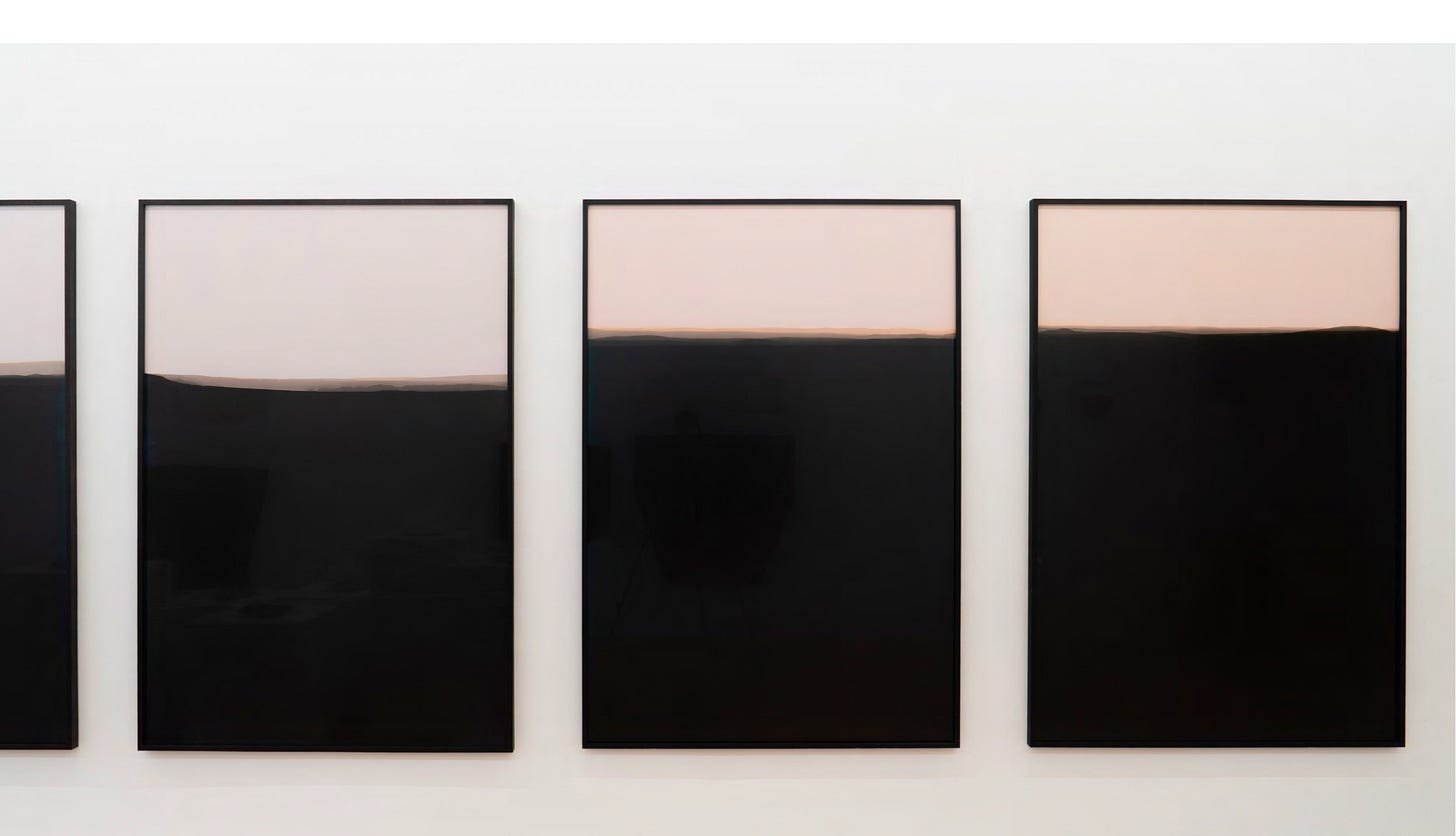

The gallery around me seems to fluctuate in appearance; plinths are arranged like rolling hills at different heights, mirroring photographs of soft sloping horizons on each wall. Upon closer inspection, I again realise these photographs are entirely devoid of a picture: glossy panels of exposed films coat one another, creating a hazy edge that mimics a skyline in Photographic landscapes, 2025.

Farther down the left side of the gallery, a lineup of opaque shards set on brown boards create a second oscillating edge, this time at the bottom border of each piece and the wall. Glass Pieces, 2025, takes influence from the photography of Antoin Sevruguin, who extensively photographed Iran during the Qajar period, but whose work was mostly lost to time due to confiscation and vandalism. The photographs captured within these fragments are barely traceable, marring the rim of each piece like pale impressions.

A pattern is fast emerging: many of these unique techniques don’t actually employ developing a photograph of a subject. Instead, the artist is seemingly fond of a vague approach. Interested in semiotics, Samavatiam works to create a network of indexes within his works. Hence, the shadows, traces, and sloping borders remind the viewer of movement, mountain ranges, and works lost to time. The success of this staging is born from the ability to turn almost anything into an index. As the viewer, nothing that I see in a gallery is perceived in a vacuum, and my personal influence can be relayed to everything. In this small stroke, Samavatiam makes his photographic work deeply individual, even as he insists on intentional ambiguity.

Hessam Samavatiam. (2025) Photographical landscapes. Photographic RC paper, photochemically treated.

Hessam Samavatiam (2025) Glass pieces. Self-made photosensitive paper wet mount behind glass, analog photographic process.

If these pieces, devoid of almost any photographical evidence, are moving, the basement of the gallery proves the artist is as confident and flexible with a fully developed picture. The flight of the stairs leads to a darker, quieter series of rooms, where I am immediately taken with an illuminated piece across from me. The photograph, Plaster Cast #23-4, 2023, depicts an eloquent, sloped archway that frames an archival Iran. Salvaged negatives of Samavatiam’s grandfather are developed onto a multidimensional plaster panel whose tectonic plates seem to crash recklessly. The photograph is nestled within these shifting spaces, negotiating a new perspective that accommodates the plaster setting.

I am entranced by this picture. Its dynamism is fuelled by an unorthodox levelling of space that facilitates movement in what would otherwise be a much more static photograph. I ponder on whether the people walking at the bottom of the picture are unaware of the deep fragmentation happening above their heads, or simply in a hurry to escape its midst.

Hessam Samavatiam (2023) Plaster Cast #23-4. Plaster, Pigment, photosensitive emulsion, analog photographic process.

Influenced by a range of Iranian, Persian, and Western photographic techniques, Samavatiam references Barthes’ ‘punctum’ as a point of reference for many of his works. The opacity and vague nature of his works point to his expectation that the viewer will focus on their own individual instinct, and not concept or studium. Maybe this is why the gallery offers a much shorter press release in house, but a lengthier explanatory text accompanies the catalogue online. With this in mind, I won’t parse the works any further, and instead conclude my appreciation of the eclectic usage of photography in this exhibition.

*Images courtesy of Ab-Anbar.