There is something unapologetically genuine about exhibiting art in a toilet. If only Duchamp could see us now- and yet, the actual scene presents itself as intriguing and ingenue. But the implications of showing art in a public bathroom, like RCA student collective Shit Show tackles, are dealing with a transient space. What are the best ways to activate such a location, and use it for a daring exhibition? In contrast, how can the more traditional gallery space Belmacz find itself still curating the exhibition Holding Places with liminal considerations in mind, but no need of such a facility?

More and more, contemporary art has begun to employ liminality and non-places in our society to explore new ways of displaying art. Marc Auge was among the first to discuss the concept in his book Non-Places: an Introduction to Supermodernity. He explains how if some places, such as homes, or community centers, are places tied to unique cultural experiences, non-places are those places that have been overloaded with diverse cultural meaning, and therefore desensitize the viewer, creating what Auge coins as ‘supermodernity’. He describes the numbing, transitional effect of a non-place: “The space of a non-place creates neither singular identity nor relations; only solitude, and similitude.”

Now, let us return to the public restroom.

At Shit Show, a familiar modality seems to be cultivating in this neutral space- at the edges of the bathroom, a scene all too organic for most not to recognize. Small groups of friends are snowballing, huddled as if they are hiding away in the last stall at the club. It’s a sense of community that the curators Isabelle Enquist, Daisy Magnusson, and Tamara Manova strived to foster, hoping that, in taking a neutral, transient space, and reinterpreting it, it would encourage such connections.

The viewers are spurred on by performances such as Oluwarotimi Shogbola’s Sonic Lessons Vol. 3: Shit Mixes- a DJ set and soundscape, that has been introduced into the quieter restroom environment, challenging it’s usual neutrality with the artist’s subversive narratives surrounding the African diaspora. For today, the music is coming from within the bathroom, pulsing its way across the hall to where a broadcast is set up, live-streaming the activities in the last stall.

Maybe one of the things that has evolved the space the most is allowing each artist to take their personal experience with a setting such as a public toilet, and reflect it openly back onto one. This creates for such an apparent mix and match of feelings and identities that can’t seem to be ignored on such an openly blank canvas. Yet, surprisingly, they don’t clash as much as you’d expect. Magnusson describes this effect, speaking to the strangeness of sitting on a toilet in a public restroom, listening to the intense DJ set in the next stall, and then looking over their head to see Don’t Flush Now by Rita Fernandez Gutierrez. All at once they are transported to a night out, while looking at a charcoal drawing, while still in the in their stall. This same strangeness, like a very vivid patchwork quilt, is forming the grounds for the small herds of peer groups, collecting in the bathroom to laugh and experience the art, the genesis of a complex landscape of cultures and social qualms laid out seamlessly, if with a messy style, across an originally anonymous resting ground.

Rita Fernandez Gutierrez, Don’t Flush Now, Ink, Charcoal.

I am particularly interested in the different methodologies employed by Shit Show and Holding Places when it comes to anonymity, and liminal space. If Shit Show spends its time developing an organic network by pointing to the functional aspects of its chosen liminal location (bathroom), Holding Places magnifies the transient qualities of the Belmacz gallery space and uses art to simply highlight these features. Implications, ambiguity, and negative space are employed heavily here to allow the viewer respite as they look at their environment. Instead of hanging artwork, artist Aaron Amar Bhamra lets a crossline laser mark the wall and pinpoints each line with an alarm clock needle in untitled, 2024.

Aaron Amar Bhamra, Untitled, 2024. Four alarm clock needles, staple, crossline laser.

Time seems to frame each piece in Holding Places. Artist Carla Ahlander discusses how her photography has changed over time to build narratives that may hold elements of fiction. She describes: “Most of the time, the scenes remain unexplained: they have no beginning or end and have not been ‘resolved’.” It is this same ambiguity that allows the pieces to don the near empty gallery space so well. The back wall of the gallery, covered with mirror paneling, is broken up by Construction of a Memory, a picture of a woman cutting gnocchi dough. Her hands are visible, but her face is not. A divot in the wall breaks the photo in two, further shaving down the frame. In a different corner of the space, we meet a photo of a curtain with a rim of light clearly visible shining from beneath it. “What you make of this, of course, is an individual response,” explains Ehlender. Each viewer must make their assumption as to what might be on the other side.

Carla Ehlender. Untitled (Curtain) From my Retrotopia, 2022. Glicee print of a scanned 35 mm negative.

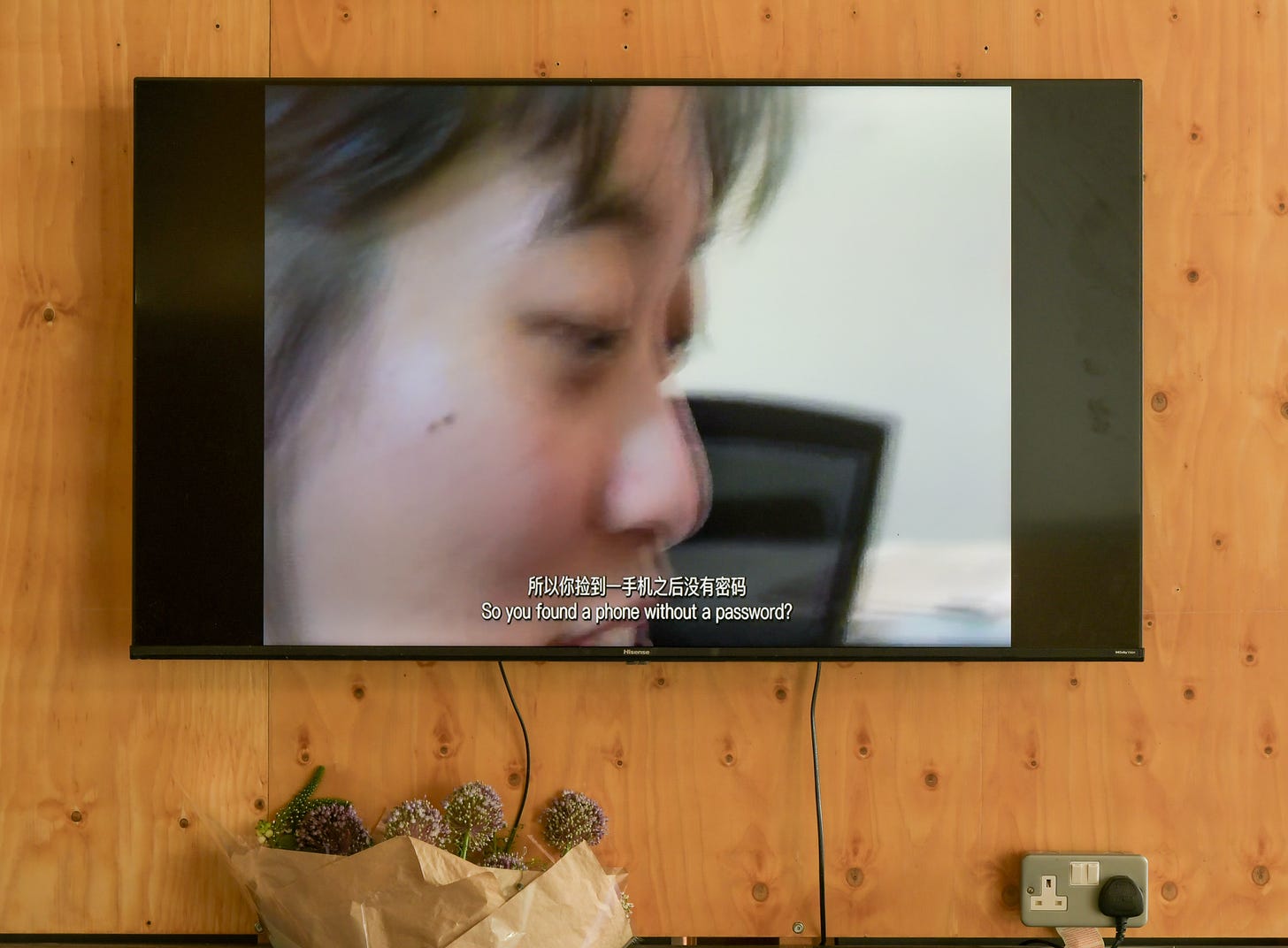

There is a similarity between the narratives created here and those fictionally composed for some of the pieces in Shit Show. Where Ehlender prefers to stage or frame reality for the purpose of an ambiguous nostalgia, artist Jida from Shit Show takes one step further, developing a fictional “mockumentary” with an enticing storyline to allow the viewer to explore the moral ground around privacy in an increasingly digital age. When I found a Phone in a Bathroom takes advantage of the exhibition’s location to lay the ground for a complex narrative with a resolution unique to each viewer’s code of ethics.

Jida, When I Found a Phone in a Bathroom. Video (14’00”).

It is clear that at first glance, Holding Places and Shit Show are two wildly different shows. One is in a clean, sleek gallery space in Mayfair. One is in a public toilet, and has adopted a more “shabby-chic” feel. Then again, I don’t know how much point there is dressing up a toilet: each show is paying clear homage to its location, in an entirely separate way. It just so happens to be that both locations are transient and liminal enough to create a lot of the same effects, and effectively celebrate two different non-places in our everyday lives. While Holding Places delivers a quiet, contemplative exhibition that respects the original space and the often forgotten in-betweens, Shit Show creates a community space that still observes the anonymous nature of the public restroom.

Pictures courtesy of Belmacz and RCA collective Shit Show.