JGM gallery, a step away from Battersea Bridge, is a carefully considered space that opened in 2017 at the helm of Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi. As an expert in First Nations artwork and a current trustee for FANZA, the Foundation for Australian and New Zealand Arts, Guerrini Maraldi has founded the gallery with the intention to focus on working with Indigenous artists who currently reside in Australia or the UK. Most of all, the gallery emphasizes contextualization and deeper understanding of individual artistic practices and techniques within the First Nations, and strives not to paint the artists exhibited with a single stroke, taking time to discuss their separate concerns and methodologies through a series of publications that accompany each show. During my visit, the gallery space held a series of texts: Revelation and Concealment’s exhibition press, along with a velvety summerly review from the gallery, featuring interviews and more exposition with artists from recent exhibitions. Here I found a detailed conversation with Hubert Pareoultja, who is currently exhibiting Looking Towards the James Range (2023).

Revelation & Concealment is a great introduction into the varied techniques that JGM’s artists employ in their practices. The gallery space is adorned with various paintings, often including vivid color schemes and allusions to what may be maps or geographical landscape. It is clear, even without knowing the artworks, that their collective intent is for the focus to be placed on the environments represented.

Watson Corby, Kalipinya Tjukurrpa (2017). Acrylic on Canvas.

I was particularly taken aback by Kalipinya Tjukurrpa (2017), by Watson Corby. This piece immediately tells a story, implying some form of movement and further narrative. The painting is a recount of a rain and hail making ceremony in Kalipinya, a well to the north-west of Sandy Blight Junction that is referred to by the Nakamarra, Tjakamarra, Napurrula and Tjupurrula men and women as the Water Dreaming Site. It is an important waterhole for spiritual purposes to these communities, and has famously inspired other paintings such as Water Dreaming at Kalipinya (1972) by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula.

Spirituality is a recurring pattern in this exhibition, often clearly defining the connection between the artist and their home. Artists such as Nyarapayi Giles use bold color and historic context to interlace ceremonial tradition into the geography of their paintings. Warmurrungu (2017) is distinguishable by the large circles used almost in topographical fashion to show a large overview of space at once. Designated colors are associated with cultural landmarks such as Karrku (Emu Dreaming) and other spaces in the Ngaanyatjarra lands, creating a vibrant homage to the Tjukurla community.

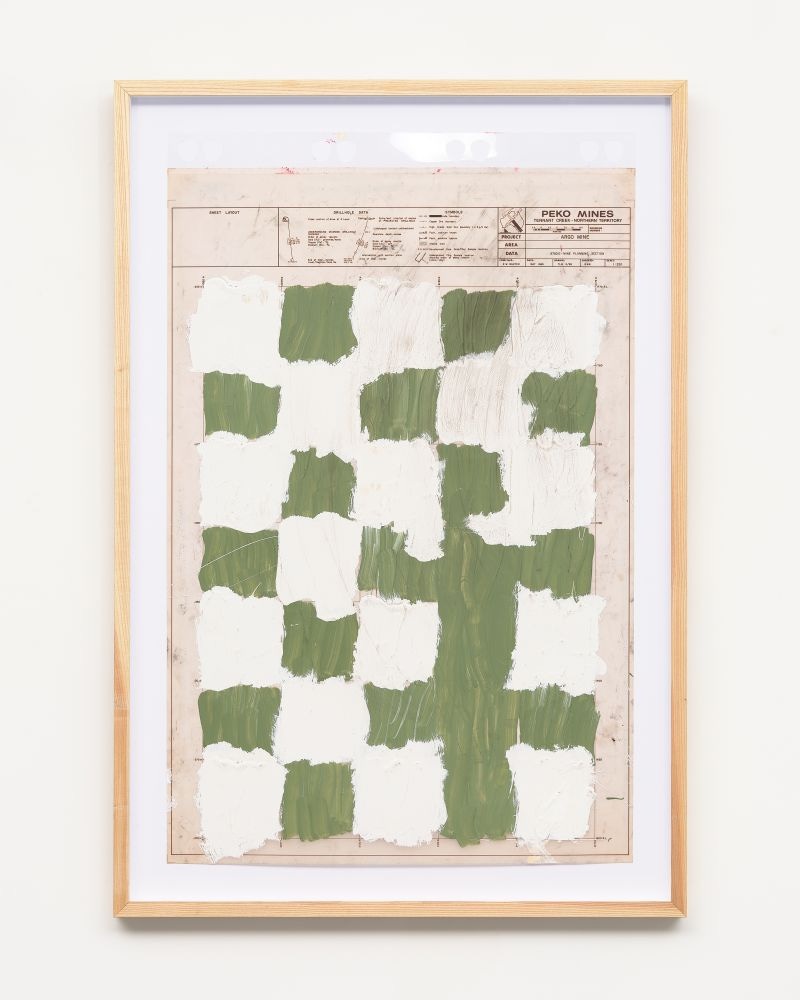

This sort of aerial view seems to be a common theme in the work of the aboriginal artists in the room. They encompass an entire landscape, and place importance on the entire environment. Marcus Camphoo’s painting Untitled II (2023) is painted over a mining map from Tennant Creek, largely obstructing the viewer from seeing the whole of the underneath. This loose yet defiant form envelops the linear grid with its soft and informal nature. The artist’s choice to paint his expression of his surroundings is not a refusal of western presence in the area, but an accurate depiction of how he envisions that nature coexists with the mines hidden below the acrylic.

Marcus Camphoo, Untitled II (2023). Acrylic Paint on Mining Map.

Almost every work in the gallery uses a viewpoint from above, aside from one painting. When I first saw Looking Towards the James Range, I was struck particularly by its unblinkingly bright colors. However, I was more drawn towards other paintings in the exhibition that were abstracted, largely out of a sense of intrigue. It wasn’t until I read Pareroultja’s interview that my interest was piqued. Of course, this is a matter of taste: I happen to enjoy abstractions more than landscapes on the whole. But the takeaway is that I am particularly grateful to the added attention to detail, and contextual information from JGM’s review that allowed me to form a relationship with the piece. Reading the description of the artist’s technique by biographer Ken McGregor, I became enticed particularly in the dual nature of his work, using a technique forged and practiced by both the Hermannsburg mission that had been established on the Finke River and the Arrernte people, who had lived there for 30,000 years. Ken explains how before the combined influence of the Arrernte and the Hermannsburg mission, there were no First Nation men who used a first person perspective like in western paintings.

Pareroultja’s beautiful and doting landscapes are a reflection of how both cultures shaped him, and how he has honored his land and tradition throughout his own life and spiritual practice.

Pareroultja describes: “ Yes, I never feel alone because the ancestors are watching me, looking after me. I believe in that, and I believe in church. I believe in both ways. In my country, when I walk around, I don’t feel fear. They are looking for me. I can feel it.”

Hubert Pareroultja, Looking Towards the James Range (2023).

It is particularly interesting to see how different the approaches of Pareroultja and Camphoo are when involving western influence in their work. This sheds further light on the name of the exhibition, Revelation and Concealment. Something about this reminds me of photography, and the choice of what remains in frame. The show centers itself around give and take, and each artist chooses what to keep in the picture. JGM gallery finely balances each artist’s methods while publishing further context, exhibiting a truly complex network of Indigenous artists.

Pictures courtesy of JGM Gallery.