This week, I visited Youngju Joung’s recent exhibition Way Back Home at Almine Rech. The gallery is located in central London and focuses on exceptional upcoming painting, encouraging the practices of multiple emerging artists as well as their long time representation.

Entering the gallery space feels like removing oneself to a different time of day. The space still benefits from the sun streaming in from the wide windows, yet its contents casts a new glow. A line of paintings streaks the room with a different light, creeping like candlelight in the dark gloom of each piece. These contained, luminous hubs are huddled between small boxy houses with shadowy depths. I am transported to an evening and the cozy warmth of home, but simultaneously, I feel as though I am sitting on the hill above the town depicted in these paintings, looking down into the dwellings below.

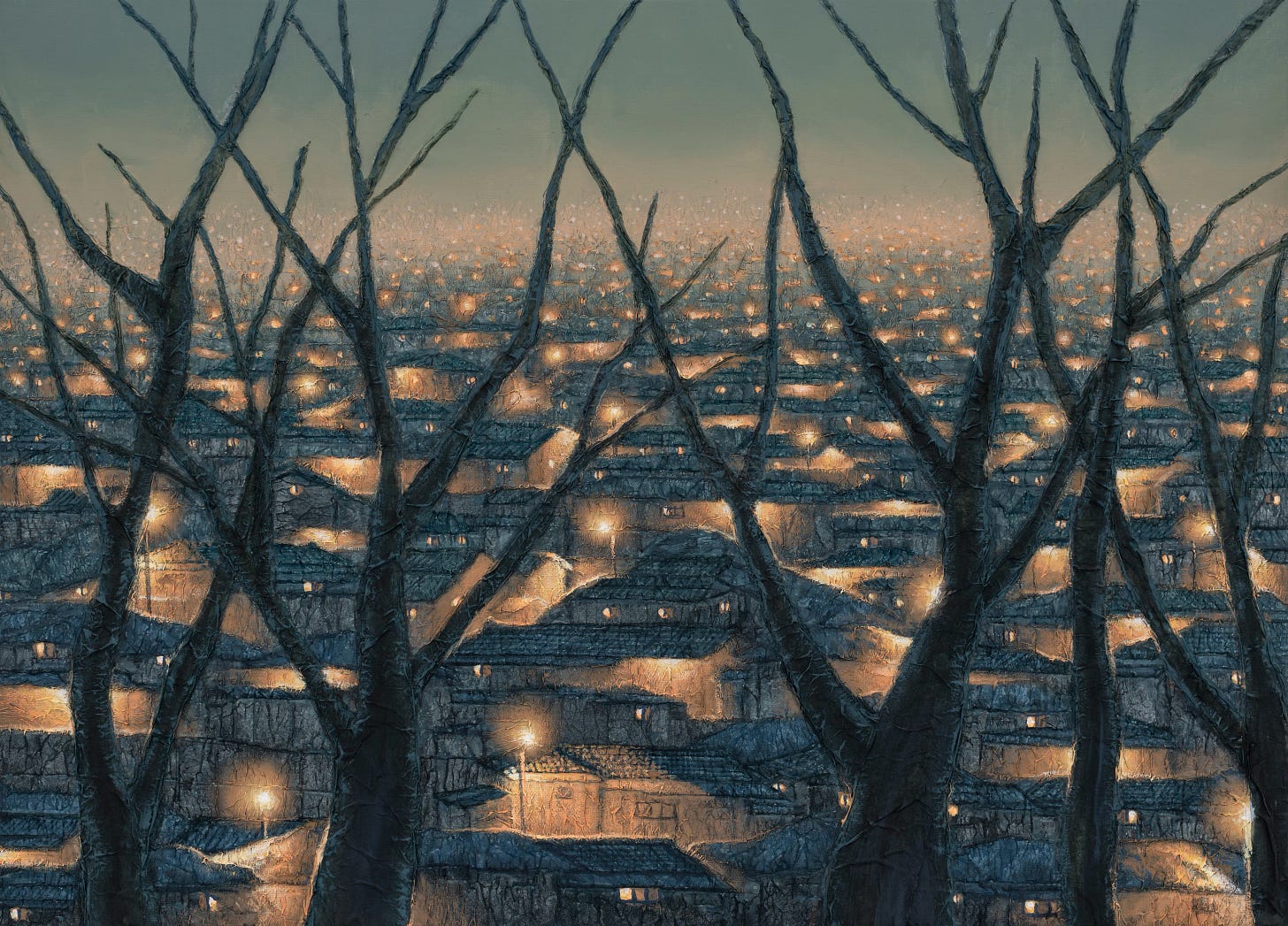

The usage of warm hues through pink, green, and yellow tinged landscapes only emphasises this effect. From far away, the paintings seem to glint as the lights gleam securely. I walk nearer. Up close, the picture changes. The careful blending of paint that allowed that hazy effect of light looks strangely muddy now. Meanwhile, the houses begin to fall into sharper focus, a rigid textural pattern like strict, crossed lines covering each building and casting it in isolated shadow.

YoungJu Joung, Spring Series, 2023, Acrylic and hanji paper on canvas.

Youngju Joung’s landscape is soft and cutting at the same time. The artist depicts emotional and societal ties to Korean shanty towns such as these, and their local communities, who she personifies using warmth and light in her paintings. Shanty towns first began to crop up in the post-war era as a needed commune for new refugees. Also called moon villages, they sometimes attract tourists as they live in the shadow of the respective cities that redevelop in their wake. Newcomers are quick to see both the beauty and the harsh conditions of these towns. Some moon villages, such as Gaemi, have seen enriching projects for murals that attracted the title of “Future Heritage Status” from the city of Seoul, but less tangible actions to echo these words. As old moon villages are quietly phased out, inhabitants live in fear of new planning for luxury housing over their heads.

In the front of the gallery, I notice there is a painting where the valley landscape of houses and lights is overshadowed by the boughs of dark, interlocking trees. Originally, moon towns were known as “Panjachon” or “wood board village”. While nowadays some newer shanty towns can range in building materials, depending on the haste of the inhabitants in creating housing, moon towns were originally built with mulberry wood and hanji paper using techniques dating back a millennia in Korean history. This soft, durable paper was used not only for printing and writing: its absorption, insulation, and sound proofing meant it was ideal for generations of house building.

YoungJu Joung, Between 427, 2024, Acrylic and hanji paper on canvas.

Using a method of combine within her painting, Joung incorporates a process of “building” using hanji paper as well. She applies it to the structure of her houses, creating a slightly haggard wrinkled appearance in places, while keeping a strong crosshatching pattern in others, conveying both the decay and preservation present in the life cycle of many shanty towns. Their security and refuge is not forgotten in spite of these communities’ shared existential threats.

The fragility of shanty towns is not the focus of Joung’s practice. The artist strives to show a visitor the local Panjachon, and the warm shelter it has supplied for so many displaced communities. Her materials speak to the practicalities of house building, and the elements at the core of a robust, consistent home.

*Images courtesy of Almine Rech.